by Rajeswari Satish | Aug 20, 2019

Spending two weeks in Indonesia as a cultural tourist entails repeated exposure to Javanese and Balinese gamelan music. Gamelan is played at museums, restaurants, hotel lobbies, and airports, either live or recorded. Indonesians take pride and effort in showcasing this national heritage art, and this is particularly palpable at public places.

Gamelan musicians at The Royal Sultan Palace

Yogyakarta playing for shadow puppet theater

Me sitting in front of the full gamelan instrument set

A full gamelan ensemble consists of a number of instruments (gongs and metallophones struck with mallets, the wooden xylophone gambang, the two-sided drum kendhang, the bowed rebab and more). Sometimes only a few of them are in action, especially in smaller settings that perhaps cannot afford to hire an entire troupe or own a large number of instruments. Occasionally, it would be a single rindik, a bamboo xylophone, playing at hotel or museum lobbies.

Small gamelan ensemble at a hotel lobby

A small gamelan ensemble at the entrance of the Ramayana ballet at Prambanan. They invited me to sit in and try out the gambang for a few minutes.

Gamelan artist playing the rindik at a hotel lobby. What scale do you hear?

In a gamelan ensemble, musicians play their individual stroke sets on their instruments to produce an orchestral effect. Gamelan is a communal activity, not a place to display individual virtuosity. Every community or village has a gamelan ensemble, played at temples, weddings and other festivals.

It was Mohanam that caught my attention first, during the ‘wayangkulit’ (shadow puppet theater) enacting Ramayana at the Sultan’s palace at Yogyakarta, with live gamelan music. No matter the type of music, a Carnatic musician (or enthusiast) has no escape from hearing it as a ragam! The brain quickly sets a tonic note depending upon what note I am considering my “Sa” at that time, a choice probably influenced by the note held the longest or played most repeatedly. It then quickly puts the notes together as a ragam scale. The next day I heard SuddhaDhanyasi at the Ramayana ballet at the magnificent Prambanan temple. My husband Satish would hear the same notes as Madhyamavati, SuddhaSaveri or Hindolam.

Carnatic musicians know that this is the ‘grahabhedam’ (tonic shift) effect, as each listener hears a different ragam, depending upon what individual mindsset as the tonic. Perhaps I should say Carnatic scales and not call it a ragam, since neither gamakams nor characteristic phrasing, both essential to form a Carnatic ragam, exist in gamelan. In gamelan, there is no background drone that maintains a tonic or ‘aadhara shruti’ as we call it in Carnatic music. Here is a typical set of pitches I heard frequently at gamelan performances:

Carnatic musicians know that this is the ‘grahabhedam’ (tonic shift) effect, as each listener hears a different ragam, depending upon what individual mindsset as the tonic. Perhaps I should say Carnatic scales and not call it a ragam, since neither gamakams nor characteristic phrasing, both essential to form a Carnatic ragam, exist in gamelan. In gamelan, there is no background drone that maintains a tonic or ‘aadhara shruti’ as we call it in Carnatic music. Here is a typical set of pitches I heard frequently at gamelan performances:

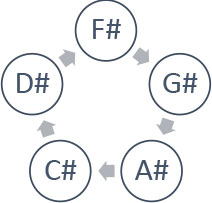

Starting from F# as my initial tonic and moving clockwise, we get the following raga scales:

Mohanam (SRGPD = F#, G#, A#, C#, D#).

Madhyamavati (SRMPN = G# A# C# D# F#),

Hindolam (SGMDN = A# C# D# F# G#),

Suddhasaveri (SRMPD = C# D# F# G# A#)

Suddhadhanyasi (SGMPN = D# F# G# A# C#).

Traveling from Java to Bali, I began hearing GambheeraNattai very often. Sure enough, my husband would hear it as Bhupalam! I heard Hamsanadam the next day but realized that they were playing exactly the same set of notes as the previous day. What do you hear here??

Clip from gamelan musicians playing at Ubud Palace before the start of a Mahabharata dance

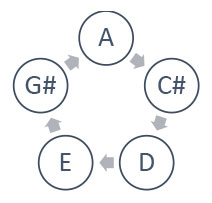

The alternate tuning system I heard results in a different set of pentatonic Carnatic ragas.

The alternate tuning system I heard results in a different set of pentatonic Carnatic ragas.

Here, we have GambheeraNattai with A as the tonic moving clockwise. Similarly, as explained in the earlier set, we generate the ragams Bhupalam, Hamsanadam, Neela (rarely heard) and unknown 1 by taking C#, D, E and G# as our tonic respectively.

The combination I call unknown1 (G#, A, C#, D, E), does not yield a Carnatic ragam. The intervals just don’t make sense.

If you are interested in learning more about gamelan, start with this primer by Prof. Sumarsam, gamelan artist and scholar from Wesleyan University. As you read it, you will discover that the gamelan tuning system is quite complex and cannot be exactly equated to the pitches of a Carnatic ragam. On certain occasions, only four pitches are sounded in an octave and my Carnatic imagination fills up the fifth to make up a ragam.

These are my musings based on a few days of gamelan constantly playing grahabhedam in my head while in Indonesia. This is my interpretation of the music that I heard with my Carnatic ears, obviously neither a technical nor a scholarly read. The excitement of hearing a variety of Carnatic scales in Indonesia had to be shared!